A Lean Penny Game for Cross Functional Teams

The Original Inspiration

In his seminal work on the Theory of Constraints, The Goal, Eli Goldratt’s main character, Alex, goes out on a hike with his son’s scouting group. While on the hike, Alex is preoccupied with work and a lot of new concepts that he’s been learning relating to constraints in his manufacturing line.

When the group settles in for a break, Alex invents a game for the scouts to play so that he can test some theories he’s come up with during the hike. He recruits some of the scouts to play the game by saying that the winners won’t have to help with the evening’s dishes.

The game is simple. Each scout has a bowl representing a workstation. Their jobs are to move matchsticks through their workstations. Each scout can only pull matchsticks from the bowl to his left, and the number of matchsticks he can pull is determined by the toss of a die. As the scouts play the game, bottlenecks emerge but move from one station to another because of the natural variation. Alex also notes that, as a result of these bottlenecks, the “work” falls further and further behind the longer they play.

Another Penny Game

I wanted to adapt this game to illustrate how a team could improve their flow by introducing cross functional team members. I Googled around to see if something like that exists, but I didn’t find exactly what I was looking for. However, I found an Atomic Object blog post that showcased something close and even pointed to an online version of the game.

It came from a book called Velocity (which I haven’t read yet) and was meant to illustrate how constraining each work station, i.e., introducing WIP limits, can improve flow.

Bringing It All Together

The team I was working with at the time was having a hard time letting go of resource efficiency, so rather than introduce WIP limits I wanted to illustrate how important it is for people to work outside their comfort zones. We played the first round just like the Atomic Object version.

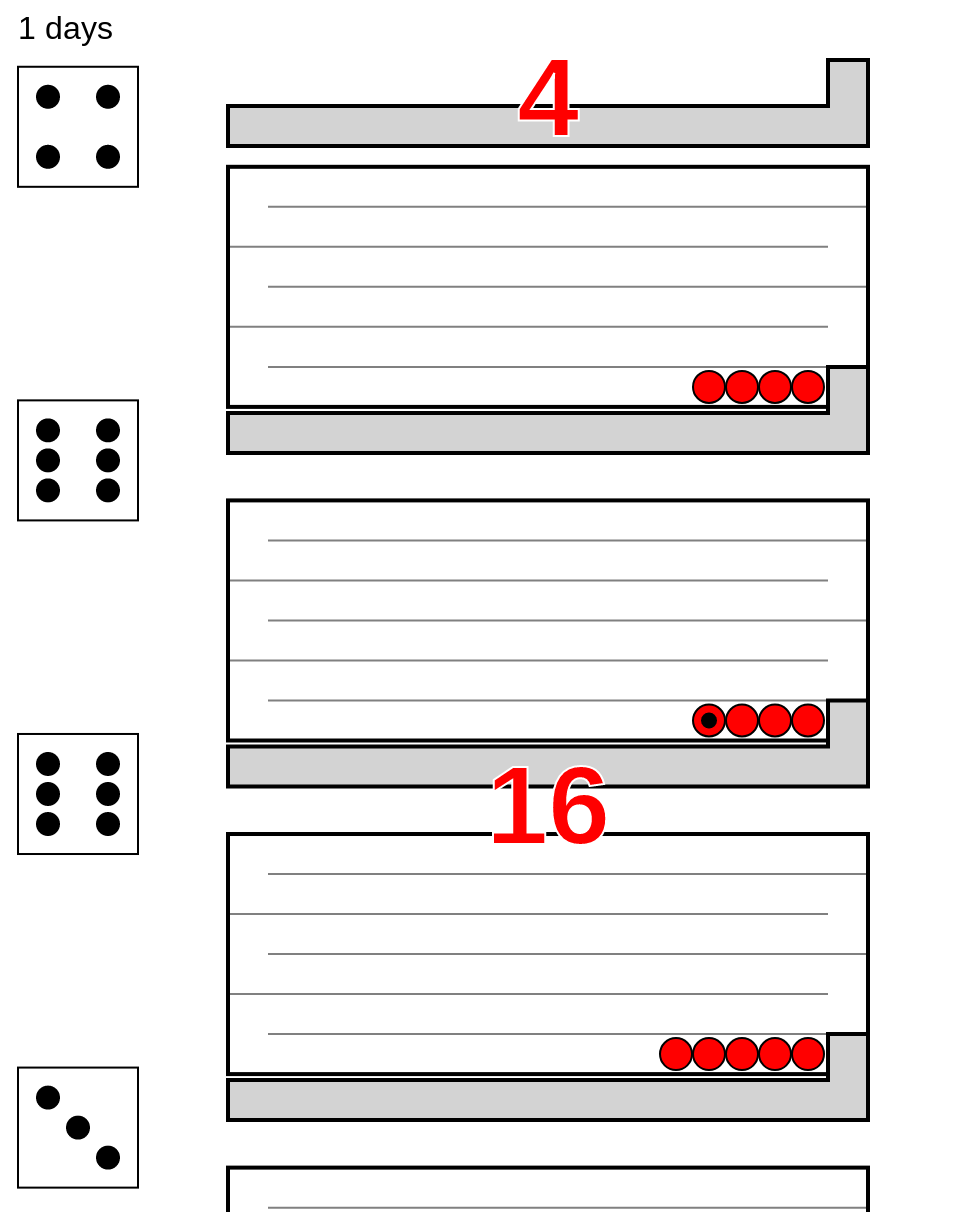

- 4-6 players per team.

- Each player starts with four pennies.

- Every “day,” each player rolls a die to determine his or her capacity.

- The player moves pennies to the next workstation based on the number on the die or the number of pennies that he or she had at the beginning of the “day,” whichever is less.

- 10 “days” of “work”

- The last person in line keeps track of how many pennies are released each day.

At the end of 10 “days,” we noted that the overall WIP in the system had grown. We also noted that the average number of pennies that were completed each “day” was about 2.5, significantly less than the mathematical average die roll of 3.5.

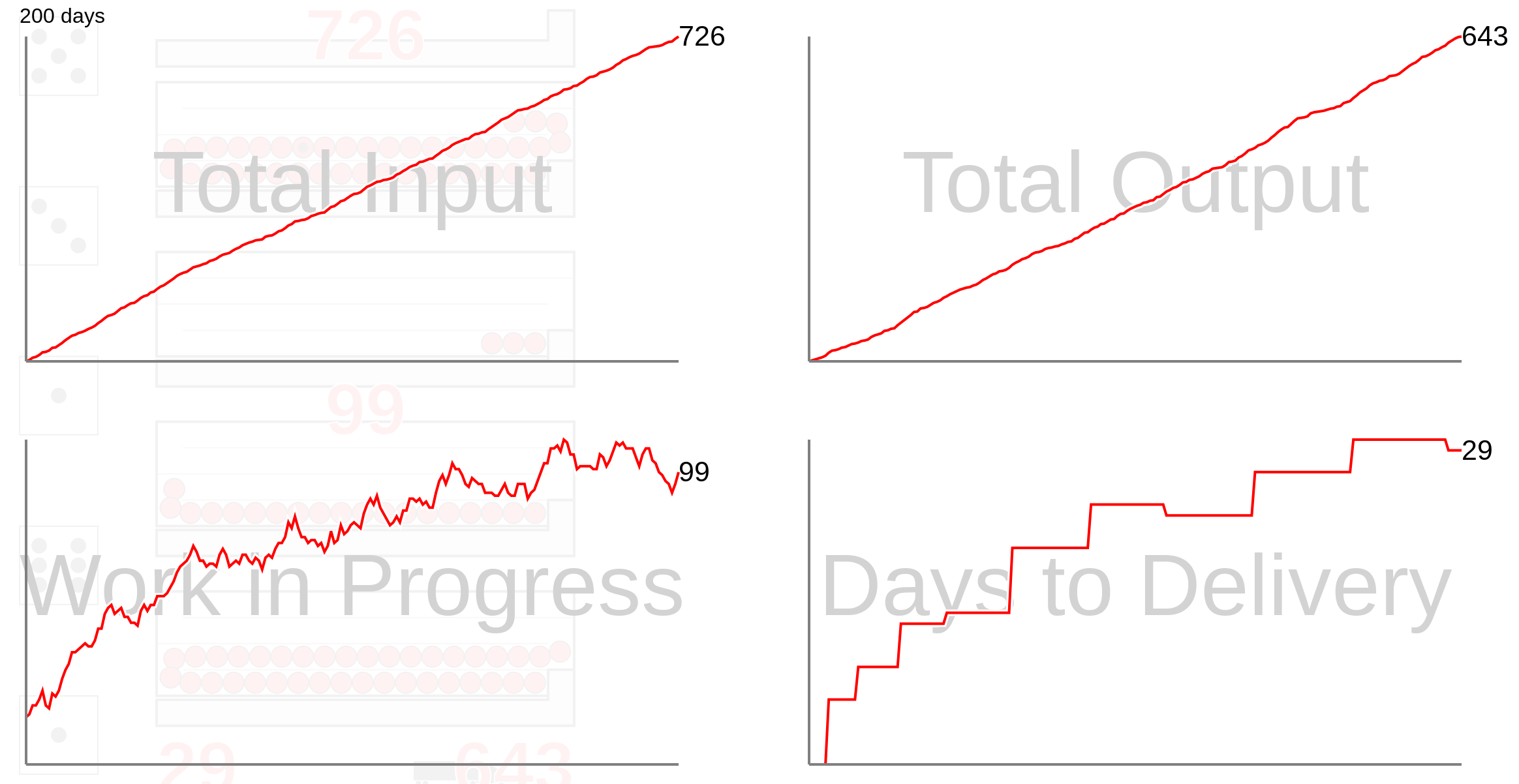

After that, I showed the team the automated version of the game to illustrate that this wasn’t a fluke. I ran the game for a “year” so that the team could see how the WIP not only grew steadily, but also had a solid correlation to delivery time.

After that, we reset the board and ran a modified version of the game for another 10 “days.” I added three new rules:

- Players could work outside of their main workstations.

- Any player working outside of his or her main workstation would receive a one point penalty to his or her capacity. E.g., if the die showed a four on a given “day,” the player could only move three pennies. If a player rolled a one, he or she wouldn’t be able to move any pennies.

- Before rolling each day, the players could have a stand-up to determine who would work on which station.

This time, the group was able to keep the WIP and corresponding delivery times down. We also noted that we minimally affected the overall number of items delivered. There was a small dip and that’s all. We all agreed that this could even be an anomaly. There was a brief discussion about whether or not it would be worth it to deliver fewer items if we were delivering the items faster and the general consensus was that it depends on the situation.

Perhaps one day I’ll build my own automated version that mimics cross functional teams.